Last time, I talked about a possible way of reframing our students’ protestations of “I’m just not a good writer!” I really appreciate all of the comments and conversation that post has already sparked, in person and online. Keep them coming!

Today I’m approaching the good-writer question from another angle, which is actually the pre-condition for our previous concept of “All writers have more to learn.” Here it is: Writing is not natural (Concept 1.6).1

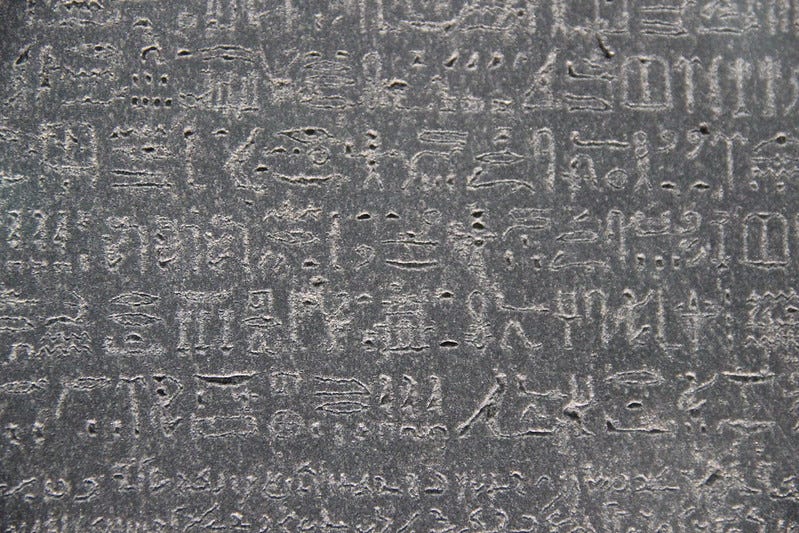

I’ll be honest: This one kinda hurts. What do I mean, writing is not natural? We learn how to write when we’re very small. We write all the time, everything from grocery lists to love letters to texts filled with emojis. And yet none of this written communication is “natural”—it’s not something we have to do in order to be human. And it’s not something we innately understand how to do; we have to be taught. For millennia, including in the present, people the world over have managed to live full and successful lives without writing (or reading) at all. Plus, there’s nothing “natural” about how the signs and symbols that make up written communication function. (Shout-out to

, whose Instagram posts hammer this point every day.)

When we’re talking about writing in the rhetorical sense, as in what we teach to students in history classes, the unnaturalness of writing is even more apparent. There are so many different ways to write history, and the conventions have changed over the centuries. There’s no one “right way” to do it. Furthermore, good writing in history is about more than just eloquence of phrase or omitting needless words. History writing is inextricable from the quality of the research, so students have to learn how to execute good writing and good thinking all at the same time. (This is, of course, true of many disciplines. But I think there’s less wiggle room in history than in some other humanities/social sciences, at least.)

You might think, my students have been writing since they were in kindergarten; shouldn’t they feel a reasonable level of comfort with the whole idea of writing by the time they get to college? I would like to think so. Obviously they know how to write letters and sentences. Many of them still struggle with mechanics and spelling and syntax (and what better proof is there of the unnaturalness of language than English spelling?). In my experience, a lot of them struggle with putting sentences into a sequence that enhances their argument rather than obscuring it. This is where the unnaturalness of history writing comes back into play.

Practice makes permanent

So, if it’s not natural, how do we naturalize writing so that our students start to feel more comfort in doing it? This is where I struggle a bit, and I’d like to hear your thoughts. My general thinking is this: The only way to overcome the challenge of the unnaturalness is to do it a bunch of times. I want my students to be writing a lot. My goal is at least a little bit in every single class (even if it’s just one sentence), plus outside of class at least once a week. The vast majority of this writing goes into their notes, where I never see it. They turn in only a few pieces, and most of those I don’t return. There are only three “formal” pieces of writing during the semester, plus two exams that have essays.

However, there’s a flaw here: As I tell my children when they practice piano, if you practice doing something wrong, you don’t learn how to do it better. You learn how to do it wrong. (Or, as my mother used to say much more aphoristically: Practice makes permanent.) Undirected, un-assessed writing may reduce the unnatural feeling, but it also might encourage students to keep writing in the same way without any impetus to develop or improve. Perhaps, then, teachers ought to be assessing and providing feedback often, on every piece of writing students do. But who has that kind of time?? I sure don’t.

On the other hand, writing is thinking. (This is Concept 1.1.2 More on this in a future newsletter.) There are some kinds of writing that aren’t meant to see the light of day; they’re just meant to spark thought and help us get ourselves in order. Is this kind of writing the way to naturalize students to the idea of putting their thoughts on paper? I think it is. But I’m not so sure that it’s the way to naturalize the kind of writing that we ultimately ask students to do in history classes. I can’t help wondering if, when I’m encouraging the “barf your thoughts onto paper” mode of writing without asking students to account for their rhetorical choices, I’m setting them up to be able to do the kind of writing that our discipline requires.3 In other words, does informal writing really improve formal writing?4

I read recently about how students distinguish between “academic” and “creative” styles of writing, where they associate academic writing with the communication of knowledge, and creative writing with the generation of knowledge. Academic writing hewed closely to specific forms of writing, with students believing that success in that area meant mastery of the forms, whereas creative writing was about developing a writerly identity.5 A student might begin to break down their discomfort in writing by learning the form of the “research paper,” for instance, which is a skill that they assume they’ll be able to carry over to another history class. Hopefully in that second class they can then focus more on the generation of their historical knowledge rather than simply its communication. However, Hutton and Gibson argue that students who think of writing in this way are less able to transfer their critical thinking and writing skills outside of a narrowly defined form. (For example, I’ve seen students who write a reasonably good short essay as an out-of-class assignment, so I expect a similar result from them on an exam essay with a slightly different prompt and…they don’t deliver.) Furthermore, they usually assessed their success based on their grade or other external feedback, rather than on their own sense of whether they had been effective.6

Generate v. Communicate

I want to tell you about one example of how historical writing can encompass both the communication of knowledge and the generation of knowledge. But I’d like to hear your ideas about whether this even makes sense.

Every semester in my American Naval History class, we work with the Naval Academy Museum on a semester-long project where every student selects an artifact off display at the museum, writes a label text for that artifact, and then ultimately writes an argument paper/text that connects to the artifact. Every semester I’ve done that last step a little differently, but the first two pieces stay the same.7

The first step is a quasi-generative step. I call it the Artifact Inquiry. Students go to the museum, look at their object for a long time, and then write about what they see.8 I ask them to communicate the details of the object in front of them, but I also tell them they’re not allowed to look up anything about it. They have to simply speculate about the things they don’t know. At the end, they have to write a list of questions that looking at the artifact has prompted in their minds. The goal is to get their synapses firing, so to speak—not to find the answers, but to think about what they might be.

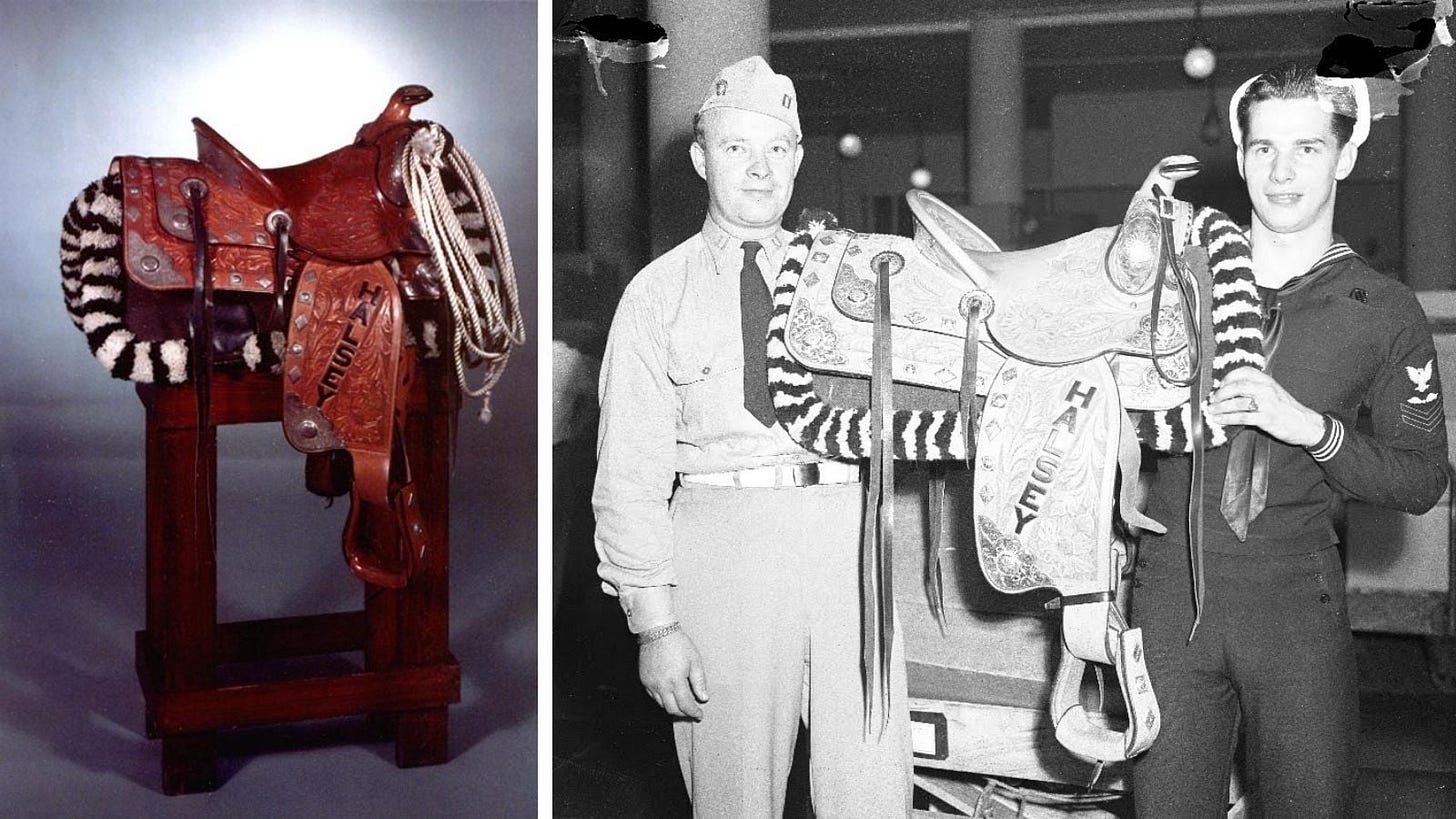

The second step is the label text (this is the step my students are on currently). This assignment has very tight parameters: 300-350 words, a hard minimum and maximum. The students must write a text that explains to a museum visitor what this artifact is, and how it fits into the story of American naval history. They write two drafts of the label text. Most of their artifacts are not spoken about at length in any scholarship, so students have to try to answer their own questions about their artifact by thinking creatively about what their artifact is, and why it matters. They get to generate new knowledge by synthesizing secondary literature and by making connections between an artifact and a bigger idea. For example, one student this semester is working on a saddle created in Reno, Nevada, for Admiral William Halsey at the close of World War II. The saddle is ornately decorated with silver workings, and it has Halsey’s name on it in numerous places. It’s a really beautiful piece—but its connection to naval history is not immediately obvious, other than that it was owned by Halsey. So the student must figure out how to explain this saddle as more than just a curiosity. (This question has a really cool answer, which you can Google, or maybe I’ll write about this saddle again.)

The first draft of the label text is certainly generative. Almost no students write with an eye toward clear communication; they almost all write in a way that demonstrates that they are using these 300-350 words to simply make sense of their artifact. They haven’t yet figured out how to organize or prioritize the information so that it will communicate to a museum visitor the knowledge they’re just now putting together.

So my feedback on the first draft, this semester in particular, focused almost exclusively on how they could organize their writing to account for how a museum visitor reads (like, make your first sentence really count because a lot of readers won’t get past it). We spent a reasonable amount of class time talking about audience on the day I returned their draft to them. Hopefully, between this general discussion and their written comments, they’ll be ready to write a second draft. This second draft should communicate to others the knowledge that they’ve generated for themselves.9

The first draft is meant to ease their own discomfort with writing in this form, for this audience. None of them has ever done this kind of writing before, and so they feel really keenly how unnatural it is. (Their comments to me in class about how hard it is certainly bear that out.) The second draft is meant to continue to ease that discomfort by making them think more about the conceptual idea behind the form (not just the word count).

Of course, even two drafts is hardly enough time to naturalize a new kind of writing. But the students love this assignment. They’re so eager to tell me about all the things they’ve learned, and they talk to their roommates and classmates about their artifact. They compare notes on weird things they see. They express pride in their ability to get within the word count. They start to believe that they can do this new kind of writing, and some of them even start to take risks with a more creative way of telling their artifact’s story. That feels like success to me, and I think it feels like success to them.

One thing that I’ve learned over the past several weeks is that there’s a lot of literature out there about writing and assessing writing! I’m only just dipping my toe into it now. So if you have run across any SOTL work about any of these topics, I’d love it if you’d share it.

In My Brain This Week

I just got a cache of books from the University of Alabama Press. The first one I picked up to read is Too Far on a Whim: The Limits of High-Speed Propulsion in the US Navy, by my friend Tyler Pitrof. I’m only a few dozen pages in, but I’ve already started revising in my head how I’m going to teach this era of naval history (good thing, since that’s coming up next week).

I’ve also been re-reading Katherine Pickering Antonova, The Essential Guide to Writing History Essays (Oxford University Press, 2020). I’ll probably have more to say about this book in a future newsletter.

Next week, I’m giving a talk for the Forum on Integrated Naval History and Seapower Studies. It’s titled “A Secret Expedition: The Burning of the USS Philadelphia and the First Barbary War.” Most of my talk will be based on my book, but who knows, maybe I’ll branch out a little.

That’s it for this week. If you like this newsletter, will you share it with someone else?

Even better, if you’re reading this and you’re not already a subscriber, will you become one?

Dylan B. Dreyer, “Writing Is Not Natural,” in Linda Adler-Kassner and Elizabeth Wardle, Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies (Logan: Utah State University Press, 2015), 27-28.

Heidi Estrem, “Writing is a Knowledge-Making Activity” (Concept 1.1), in Adler-Kassner and Wardle, 19-20.

Writing enacts disciplinarity. Neal Lerner, “Writing Is a Way of Enacting Disciplinarity” (Concept 2.3), in Adler-Kassner and Wardle, 40-41.

I’m sure there are studies about this. Someone please point me to them.

Lizzie Hutton and Gail Gibson, “‘Kinds of Writing’: Student Conceptions of Academic and Creative Forms of Writing Development,” in Developing Writers in Higher Education, ed. Anne Ruggles Gere (University of Michigan Press, 2019), 90-91, https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvdjrpt3.9. The study written about here noted that there were a few students who began to recognize that both types of writing might develop in a symbiotic relationship, but that those students were almost all writing minors who had received specific writing instruction.

Hutton and Gibson, 95.

Since I’m trying something new (again) this semester for the third step, I’m not going to write about it right now. But I’ll probably write about it at the end of the semester when we see whether my grand plan worked. Also, shout-out to USNA Museum Educator Sondra Duplantis, who goes above and beyond every single semester to locate a huge number of artifacts, prepare their accession packets to give to the students, schedule time with every one of my 43 students to help them select their artifact, and generally serve as a resource and sounding board for them. I could not do this project without her.

See Shari Tishman, Slow Looking: The Art and Practice of Learning Through Observation (New York: Routledge, 2017). I started doing this activity before I knew about this book, but I was really happy to learn that something I intuited as being a useful activity has some scientific backing.

I’m getting the second draft on Wednesday. We’ll see how they do.

1. Ask them to define "good" and "writer." While the academic qualifications to get into Annapolis are largely based on their GPAs and how fast they were able to fill bubbles on a standardized exam, remind them that they wrote well enough to persuade a Member of Congress and the Academy to consider them for a nomination.

2. Remind them that nobody is born a "good writer" just like none of them was born a "good athlete" (which is another component of their admission to the Academy!). Their athletic skills came from practice, practice, and more practice. They may have started with 10 reps, then 20, and soon 100. Similarly, their writing skills must start incrementally, practicing with short essays before writing a term paper.

3. Remind them that many cultures have oral, rather than written, histories, and that much of history consists of story-telling. For History class purposes, however, one needs to corroborate those oral stories with historical records. Ask them to interview a veteran about his or her personal recollection of a memorable event or incident, and task the student with finding records to document that event, and how to footnote those sources.

4. Finally, don't make yourself a bottleneck or chokepoint by reviewing everybody's submissions and providing individual feedback on each paper. Instead, encourage them do a bit of peer review as a class exercise. Let the students review one another's work, and to give a positive critique. The midshipmen have a natural curiosity, and will let their classmates know where further research may be needed. It will help them to see examples of good (and bad) writing, and to compare it to their own work. You might even post anonymous excepts on the screen and let the class critique them.

5. Remind yourself these are underclassmen and women with only a high-school level of historical research under their collective belts. And for those who want to go further, give them a FINHSS or McMullen paper to show them an example of graduate-level historical writing. Or ask the USNI for old copies of Naval History magazine to share with the class for examples of "popular" historical writing. :-)